The Anti-Ownership Ebook Economy

Sarah Lamdan, Jason M. Schultz, Michael Weinberg, Claire Woodcock

Something happened when we shifted to digital formats that created a loss of rights for readers. Pulling back the curtain on the evolution of ebooks offers some clarity to how the shift to digital left ownership behind in the analog world.

Introduction

Have you ever noticed that you can’t really “buy” an ebook? Sure, when you click that “Buy Now” button on your ereader, tablet, or phone, it feels like a complete, seamless transaction. But the minute you try to treat your ebook like a physical book – say by sharing it with a friend, selling it to someone else, donating it to a school library, or sometimes even reading it offline, reality sets in. You can’t do any of those things.

With most ebooks, even if you think you “own” them, the publisher or platform you bought them from will say otherwise. Publishers and platforms insist that you only buy a license to access the books, not the rights to do anything else with them. And because platforms like Amazon and Apple control most of the technology we use to read ebooks, their opinion often dictates the reality of the ebook ecosystem. Beyond controlling books, these platforms can also do several things no physical bookseller has ever had the power to do. They can track your reading habits, stop you from reselling or lending a book, change the book’s content, and delete it from your digital library altogether – even after you’ve bought it. This doesn’t happen in the print book market, where you can still feel confident that when you buy a book, it’s yours to share, sell, or simply read without it being tracked or censored.

Something happened when we shifted to digital formats that created a loss of rights for readers. Pulling back the curtain on the evolution of ebooks offers some clarity to how the shift to digital left ownership behind in the analog world.

While most publishers still sell physical books, when it comes to ebooks, the vast majority appear to have made a collective decision to shift to offering only limited licenses. Some of the reasons for this shift are economic, some legal, some technological, and others psychological – a belief that limiting or eliminating digital ownership of books will raise publisher revenues, forstall free copies leaking onto unauthorized websites, and allow publishers and platforms unprecedented control and tracking of the behaviors of readers, as well as universities and libraries that provide ebooks. Whether these beliefs map to reality, however, is hotly contested.

Just as platforms control our tweets, our updates, and the images that we upload, platforms can also control the books we buy, keeping tabs on how, when, and where we use them, and at times, modifying or even deleting their content at will.

Economically, platforms and publishers also believe licensing gives them more control over how ebooks generate revenues. For example, they currently use licensing to charge libraries for the right to lend the book to patrons, or tying ebooks to platforms that monitor user behavior, creating a new revenue stream based on selling user data.

Legally, the shift from selling to licensing attempts to circumvent centuries of law that have limited publisher control over post-sale uses of books. This law is a copyright doctrine called “exhaustion” or “first sale.” The idea behind first sale is that publishers were always entitled to make money from the first time they sold a book, but after that, the sold copy is beyond their control. The new owner can decide to resell, lend, or use the book in any manner they see fit. Licensing attempts to keep that control with the copyright owner, forever.

Technologically, publishers have turned to companies like Amazon, Apple, and OverDrive to distribute and control their ebooks. These publisher-platform partnerships presented new opportunities for publishers to remain involved in the post-sale life of a book. Just as platforms control our tweets, our updates, and the images that we upload, platforms can also control the books we buy, keeping tabs on how, when, and where we use them, and at times, modifying or even deleting their content at will. That same control also allows platforms to monitor when and how you read, which is key to new revenue streams based on selling user data.

Finally, psychologically, publisher-platform partnerships have reinforced a belief long held by publishers that with greater legal and technological control, they will reap greater financial rewards. Publishers believe these rewards flow from forcing purchasers to pay for additional uses (such as when libraries want to lend out ebooks to patrons), and by limiting how books are shared and distributed outside of their control. While it is unclear that any of these beliefs have manifested into reality, the psychology has taken hold, in part because ebook platforms have now locked publishers into this partnership in ways that make it extremely difficult to disentangle.

This report explains that, while there is nothing new about publishers’ desire to seek novel ways to increase revenues, along with control and surveillance of readers, the new publisher-platform partnership creates a mechanism to align the ebook market with those goals. That new market alignment raises questions about whether these shifts are the best option for readers and institutional book buyers, particularly libraries. It also raises questions about how the newest players in the market – ebook distribution platforms – shape things to align with their own interests.

In order to fully understand the dynamics at play, we interviewed over 30 stakeholders that fill various essential roles in the ebook marketplace, from publishers to platform CEOs to literary agents, librarians, and lawyers. We discussed the priorities, concerns, and constraints that help shape their participation in the ebook marketplace. Our goal was to understand and document how this world looks through their eyes, and synthesize those views into broader conclusions. In the following sections, we will deconstruct the shifts that have made it difficult to actually own an ebook collection, as well as the challenge that lies ahead if we wish to resurrect ownership as a consumer choice for ebooks.

Our study leads us to several key conclusions:

By turning to platforms as the primary technical means for conveying ebooks, publishers have introduced a third major player into the ebook supply chain: ebook platform companies. Together with publishers, platforms have restricted the ebook market to one composed primarily of licensing instead of sales.

The platform companies have motives and goals that are independent of those of publishers or purchasers (including institutional buyers such as libraries and schools). Rather than looking to profit from individual sales, like a bookstore does, platforms compete to collect and control the most aggregate content and consumer data. This enables what are now widely known as “surveillance capitalism” revenue models, from data brokering to personalized ad targeting to the use of content lock-in subscription models. These platforms’ goals are sometimes at odds with the interests of libraries and readers.

The introduction of platforms, and especially publisher-platform partnerships, has created new forms of legal and technological lock-in on the publisher side, with dependencies on platform infrastructure posing serious barriers to publishers independently selling ebooks directly to consumers. Platforms have few incentives to support direct sales models that do not require licensing, as those models do not easily support tracking user behavior.

The structure of the ebook marketplace has introduced new stressors into both the publishing and library professions. Publishers and libraries feel they are facing existential crises/collapse, and their fears are pushing them into diametrically opposed viewpoints. Publishers feel pressured to protect and paywall their content, while libraries feel pressure to maintain relevant collections that are easily accessible via digital networks. Both libraries and publishers feel dependent on the ebook platform companies to provide the ebooks that readers demand, allowing the platform economy (which is already dominated by only a few large companies) to have even more power over the ebook marketplace.

Because of the predominance of the publisher-platform licensing model for the ebook marketplace, important questions exist as to the impact, if any, that digital library lending of books has on that market. For example, while some evidence exists that the availability of second-hand physical books via libraries and used bookstores might compete with direct publisher book sales, it is less clear that the digital loan of a single title by a library competes with platform ebook subscriptions and locked-in book purchases. Moreover, given that publisher-platform partnerships profit from surveillance of book buyers, consumers who choose more privacy-friendly library loans may represent an entirely distinct market that places significant value on data protection.

While access to user data generated by platform surveillance of readers is a potential benefit to publishers, in practice publishers do not fully exploit (and may not have full access to) that information.

The Emergence of the Publisher-Platform Partnership

Before getting into the details of how the ebook marketplace has evolved, it is worth considering the major market players and how they relate to one another. This is key to understanding why the publisher-platform partnership has been so effective in structuring the ebook market in a way that is different from the physical book market.

The Physical Book Market

One simplified way to imagine the physical book market is as having two poles. One pole is publishers. The other is purchasers.

Figure 1. The physical book market.

One simplified way to imagine the physical book market is as having two poles. One pole is publishers. The other is purchasers.

The publishers work with authors to bring individual titles to market. It is the role of the publishers to manage the economic life of the book. Most authors hand over control of the economic life of the book – marketing, design, manufacturing, distribution – to the publishers.

The purchasers take a book out of the publisher’s control and into the world. The purchaser may be an institutional purchaser, like a library, or an individual reader who wants to own the book themselves. The purchaser may also provide others access to the books, such as public school students or library patrons. Whatever form they take, once the purchaser has purchased the book, the book leaves the control of the publisher and becomes the property of the purchaser.

Of course, bookstores (and equivalent intermediaries in the institutional context) are also an important part of this equation. They serve as a bridge between publishers and purchasers. Bookstores order books from publishers, market them to purchasers, and ultimately deliver them into the hands of purchasers.

Figure 2. Bookstores serve as a bridge between publishers and purchasers.

Bookstores order books from publishers, market them to purchasers, and ultimately deliver them into the hands of purchasers.

However, bookstores have only a transitory moment of control over the books. When they order books, they either sell them to purchasers or return them to publishers. The bookstores have no direct control over how publishers decide to create individual titles, nor do they have the ability to control how purchasers use the books, once they are purchased. In fact, all of the flows in the physical book market are essentially one way – from publishers, to bookstores, to purchasers.

The Ebook Market and the Publisher-Platform Partnership

The ebook market is different in some key ways. One important difference is that the flows in the ebook market do not move in just one direction. Swapping ebook platforms for bookstores creates a long-term connection among everyone involved in the transaction. Unlike distributors and bookstores, ebook platforms have an ongoing relationship with ebooks that extends well beyond the point of purchase. Not only do ebook platforms market and sell the books – they are where purchasers go to manage and read them. This ongoing relationship with the ebook is fundamentally different from the temporary transactional nature bookstores play in the physical book market. Instead of the bipolar publisher-purchaser physical book market, the ebooks market involves publishers, purchasers, and platforms. These nodes are in constant dialogue with each other, well past the point of purchase.

Figure 3. The ebook market and the publisher-platform partnership.

Instead of the bipolar publisher-purchaser physical book market, the ebooks market involves publishers, purchasers, and platforms. These nodes are in constant dialogue with each other, well past the point of purchase.

By maintaining contact with the ebook and the purchaser in perpetuity, platforms have the opportunity to generate new types of data about purchasers and their habits. Publishers and platforms team up to exercise levels of control over purchasers and copies of ebooks in ways that are impossible in the physical book market.

Like all partnerships, the publisher-platform partnership encompasses distinct incentives that are often – but not always – aligned. When publishers and platforms coordinate, they can shape the market in their favor by limiting traditional rights of purchasers.

Publishers and platforms share incentives to increase control over how ebooks are used, especially at the expense of the purchasers. Both can also benefit from accessing reader data, although, as discussed in more detail below, the nature of the benefits differs somewhat. Publishers and platforms also have an interest in preventing purchaser behavior that they disapprove of. Sometimes, that behavior is illegal behavior, such as large-scale pirating of ebooks. Other times, that behavior is simply behavior that the publishers and platforms see as contrary to their own interests, such as lending an ebook to a friend.

There are also times when the publishers’ and platforms’ interests do not align. Platforms have clear incentives to lock purchasers into their platform, and monetizing user data is core to their business models. Publishers have incentives to sell more books, which could potentially benefit from a diversity of platforms competing with each other for different types of purchasers. Publishers may also be less effective than platforms at fully exploiting user data, and less interested in doing so.

While these differences are important, the aligned interests of the publisher-platform partnership have been powerful enough to create an ebook market that is very different from the physical book market. This paper focuses on a number of dynamics that flow from the partnership, and changes that those dynamics create.

From Physical Book Sales to Ebook Licensing – An Opportunity for Publishers to Achieve Long-Held Goals

The markets for ebooks and physical books are very different. Some of those differences are obvious – physical books are easy to measure and identify as individual objects, while ebooks are more fluid and ephemeral as data that can be stored, transmitted, and accessed in myriad ways. Other differences emerge only when readers attempt to treat ebooks like physical books, and in doing so run into legal and technological restrictions.

As we will explain below, physical books are governed by rules of property and ownership that can be traced back centuries. These rules give people who own physical books clear rights over how they can use those books. However, the rules that govern ebooks are much less clear.

From Owning to ‘Purchasing’ (With Licenses and Tracking)

For centuries, the law has always balanced the right of an author or publisher to control their intellectual property with the right of a book purchaser to control the copy they buy. Every sale of a physical book involves an exchange. Purchasers pay money to the publisher. In return, publishers give up their ownership over that copy of the book being sold. The purchaser owns their copy of the book and can treat it as their private property, not worrying what the publisher might want.

Over the years, publishers have made many attempts to avoid this exchange, controlling both the purchase price and what purchasers do with the books after they are sold. For example, in the early 1900s, publishers tried to control resale prices on the books people bought from retailers by stamping mandatory resale prices on a book’s front page. (That attempt was rejected by the US Supreme Court). Publishers also tried to limit where people could resell books they bought, in one case claiming that a book sold in Thailand couldn’t be resold in the US. (That attempt was also rejected by the US Supreme Court, in 2013). These attempts failed because the publisher’s copyright does not give them absolute control of a book in perpetuity; the copyright system is a balance between publishers and purchasers. If publishers want the benefits of the copyright system, they also have to accept the limits it imposes on their power.

Publishers do not get to tell purchasers what they can do with physical books, because of a longstanding principle in copyright law called “exhaustion,” also known as “the First Sale Doctrine.” This rule says that as soon as a copyright holder parts with a copy of their work – whether through a sale, a donation, or even by throwing copies in a trash bin – they no longer have any claim of control over that copy. Instead, whomever comes into lawful possession of that copy now has all of the “incidents of ownership” that come with any other form of personal property. This rule is not limited to physical objects that are protected by copyright. It protects anyone who purchases any sort of physical object. In the same way that a car company cannot shut down independent used car lots and toaster companies cannot police the prices of used toasters at thrift stores, publishers cannot claim control over the copies of books we lawfully own.

Copyright law provides incentives for publishers to help produce books, periodicals, and magazines. It also supports institutions such as libraries and archives that work to preserve those works after they are sold and ensure long-lasting access.

This rule exists for many reasons – respect for personal property, market efficiency, privacy, and preservation chief among them. Copyright law provides incentives for publishers to help produce books, periodicals, and magazines. It also supports institutions such as libraries and archives that work to preserve those works after they are sold and ensure long-lasting access. For physical books, all of this happens seamlessly every day because of the First Sale Doctrine.

The advent of digital books has reinvigorated this long-running battle over post-exchange uses, with publishers claiming that they have the right to charge money for an ebook and decide what happens to that digital copy after money has changed hands.

Publishers’ Belief That Secondary Markets and Library Lending Undermine Profits

For decades, publishers have expressed displeasure over the ways the First Sale Doctrine has prevented them from exercising control over books once they were sold to customers. These critiques often target the secondary market, where used books are sold at prices, times, and places beyond publishers’ control by sellers with no obligations to report those sales back to the original publishers. After several failed attempts to challenge the First Sale Doctrine in the context of the physical book market, many of the publishers’ concerns seem now to be manifesting within the rules of ebook distribution platforms and licenses.

Economic studies paint a complex picture of the interplay among used book markets, new book sales, publisher profits, and overall consumer welfare for physical books. In some cases, the used book market may increase publisher profits because people are willing to pay a higher price for a new book they know they can sell later. In other cases, a lower-priced used copy of a book could steer a purchaser away from paying full price for a new copy. However, even in the case of consumer preferences for cheaper used copies, or borrowing books from libraries instead of purchasing them, it is unclear how often used book purchases or library loans are actual substitutes for new-book buying. Participants who work with libraries at Big Five publishing houses did recognize that libraries are sites of discovery that lead to book sales. There are also other social benefits of secondary markets, such as privacy and preservation, that can impact the analysis.

Regardless of the actual impact that a robust secondary market may have on an individual publisher’s sales and profits, for well over a century publishers have demonstrated that they believe the secondary market acts to undercut prices, sales, and profits in the primary book market.

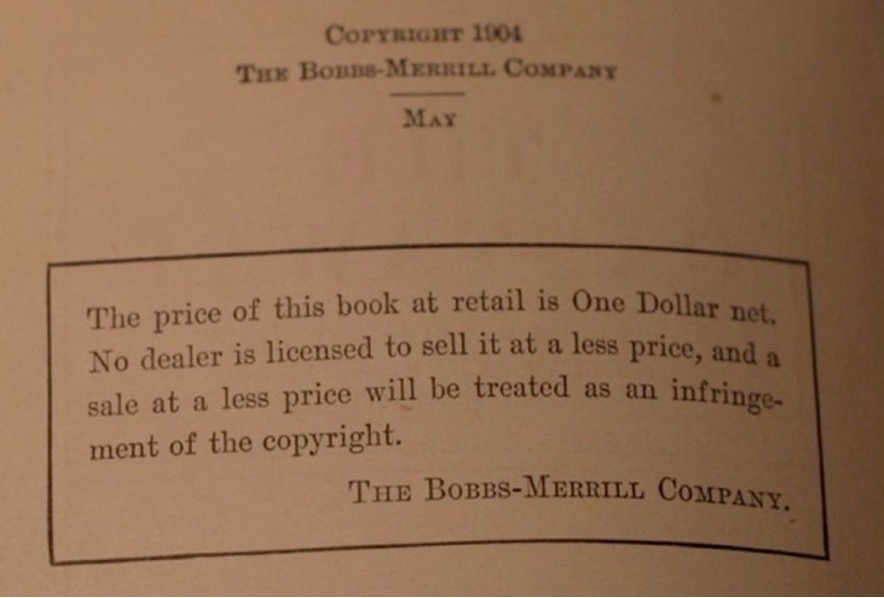

Regardless of the actual impact that a robust secondary market may have on an individual publisher’s sales and profits, for well over a century publishers have demonstrated that they believe the secondary market acts to undercut prices, sales, and profits in the primary book market. This belief that the secondary market is harming their business has driven publishers’ behavior since at least the start of the 20th century. That publisher wariness of the uncontrolled use of books is key to understanding publisher motivations as the ebook market has evolved.

Bobbs-Merrill Company v. Straus, the 1908 Supreme Court case that established the First Sale Doctrine in United States common law, flowed directly from a publisher’s attempt to control the minimum price that the novel The Castaway could be sold for on the secondary market. In that case, The Castaway’s publisher, the Bobbs-Merrill Company, added a notice to each copy of the book that no dealer was “authorized” to sell the book for less than $1. When the Straus brothers purchased a number of copies and decided to sell them for less than $1, Bobbs-Merrill sued to enforce its $1 price floor. Ultimately, the US Supreme Court ruled that Straus did not need “authorization” from Bobbs-Merrill (or anyone else) to sell the books at whatever price they chose. Once Bobbs-Merrill sold the books, their preferences for how the books were used did not matter.

This hostility toward the secondary market continued even after the Bobb-Merrill decision tamped down publishers’ legal power to limit it. In 1931, a group of book publishers hired PR pioneer Edward Bernays – the “father of spin” – to fight against used “dollar books” and the general practice of book lending. Bernays decided to run a contest to “look for a pejorative word for the book borrower, the wretch who raised hell with book sales and deprived authors of earned royalties.” The contest generated an impressive list of verbal assaults on those who would dare to lend or receive a book without paying for the privilege to do so. Suggested names included “book weevil,” “bookbum,” “culture vulture,” “book-bummer,” and “book buzzard.”

Figure 4. Bobbs-Merrill Company v. Straus and the establishment of the First Sale Doctrine.

The Bobbs-Merrill Company added a notice to each copy of The Castaway that no dealer was “authorized” to sell the book for less than $1. Ultimately, the US Supreme Court ruled that Straus did not need “authorization” from Bobbs-Merrill (or anyone else) to sell the books at whatever price they chose.

In the introduction to C. E. Ferguson’s 1969 revised-edition economics textbook, he genially declared that “[s]ince everyone knows the basic reason for a revised edition is to kill off the existing used book market, it would be idle to suggest otherwise.” Similarly, in 1974, it was reported that “[p]ublisher’s representatives have no doubt” second-hand copies of textbooks acted as “a drain on publishers’ and authors’ profits.”

Publishers demonstrated their antipathy toward the secondary market again when Amazon launched its secondary book market. In 2002, Association of American Publishers (AAP) President Patricia Schroeder told The New York Times: “I wring my hands, pound my desk and say, ‘Aargh,’” because publishers could not legally prevent Amazon from immediately offering used books for sale (at a price outside of the publishers’ control), once those books entered the market. Schroeder pleads for more control over the secondary market: “‘We asked could we at least talk about when something could become available as a used book? Could we maybe wait three months after the book was published?”

Amazon founder Jeff Bezos responded to the complaints by reminding publishers about the First Sale Doctrine: “When someone buys a book, they are also buying the right to resell that book, to loan it out, or to even give it away if they want. Everyone understands this.” In short, Bezos said tough luck – ownership confers certain rights, including the right to resell.

Having no luck in judicial courts or the courts of public opinion when it came to controlling the secondary market for physical books, publishers saw a new opportunity as they began to offer ebooks to the public. They saw ebook licenses – not sales – as a way to retain control over digital books by preventing secondary markets from developing. Platforms like Amazon, and other secondhand booksellers, cannot resell ebooks they or their users do not own. Borrowing from the software industry’s playbook, publishers adopted the practice of licensing content from ebooks instead of selling ebooks outright. By licensing ebooks, publishers could claim they avoid transferring digital ownership, which would create first sale rights for purchasers. A research study participant formerly at a Big Five publishing house explained the practical effect of this approach: “With a license, you can’t give it away. You can’t sell it. You can use it. And you can see why you have to do that. Right? Because if we sold you the digital file, you could resell it to whoever you want at whatever price you wanted. And there’s no limit.”

Although concerns about the secondary market usually are discussed in the context of used book sales, participants in the publishing industry also expressed wariness about book owners lending their books to friends. As a former executive at a major publishing house noted, one benefit of a license was that once you pay for an ebook, “you can’t give it away.”

Decades of publisher hostility does not prove that the secondary market actively harms the interests of publishers or authors. While there are publishing employees who do not seem to believe the resale of books is an ongoing concern to publishers, because they are resold through bookstores and similar venues, there is still evidence of a pervasive belief within the publishing industry that the ability of book purchasers to resell their books outside of publisher control is a problem that needs to be addressed. This belief may help explain the publishing industry’s enthusiasm for digital distribution models that eliminate first sale and the independent secondary market entirely.

Fear, Loathing, and Imitation of the Music Industry’s Digital Marketplace

The vendors and publishing workers interviewed for this study consistently cited the history of the music industry’s trials, tribulations, and ultimate transition to digital as a cautionary tale that helps explain why publishers adamantly prefer to structure all ebook purchases as licenses instead of sales. Publishers and booksellers saw music industry empires crumble in the early 2000s as open digital music formats such as MP3 became popular. Companies like Sam Goody and Tower Records shuttered their physical storefronts as people started downloading music from unauthorized sources like Napster, Kazaa, Aimster, Grokster, and LimeWire instead of buying physical copies.

For most study participants, the music industry acted as a powerful negative example of what could happen during a digital transition. It was cited by the publishers as a foundation of the current ebook market in proceedings against the Internet Archive’s Controlled Digital Lending service. “Mindful of the havoc wrought on the music industry by piracy and the uncontrolled appropriation of digital content, the Publishers developed a sustainable market for affordable ebooks with critical controls, including limiting commercial ebooks to one user account.”

Later, a senior vice president of a Hachette imprint reiterated these concerns in the same proceeding. “Many authors (and some publishers) were initially wary of entering the ebook market, in large part because it emerged in the wake of the destruction that websites like Napster caused to the music industry.”

Chantal Restivo-Alessi, the chief digital officer of HarperCollins, serves as a personal bridge between the two industries. “The ebook was developed in the shadow of rampant piracy in the music industry in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Concerns about the widespread unauthorized distribution of digital copies were front of mind when the company first began to evaluate the ebook format decades ago and have remained in the forefront of my thoughts once I joined the company in 2012. I know this history first-hand because I worked in the record industry from 1996 to 2007.”

While it is not entirely clear how this history has influenced individual decision-making, its pervasiveness in discussions around ebooks is noteworthy in and of itself. “Books are a thin-margin business,” a former executive at a Big Five publisher said. “So if you have a drop of say, 15% of people who go into bookstores, they will not be able to make it through. And so you would have what happened to music stores happen to bookstores, and nobody in publishing wants to see that.”

One study participant, who is an executive with a book trade association, believes publishers misinterpreted how the music industry was ravaged by these changes.

“There’s some aspects of what happened with music that applies to journal publishing and there are some types of books that might emulate what’s happening to journal publishing, but I think overall, what happened with music was that people didn’t want the bundle. They didn’t want the album. Most people, they wanted a song, or they wanted a couple of songs. And there was no market to create those songs until Napster came along. And Napster did it in a way that violated copyright and got it shut down but it opened the barn door to oh, we can sell songs and Apple stepped in, particularly among other [technology companies], and said, ‘Alright, we can help you, the label, sell more songs.’”

In the early 2000s, Amazon experimented with the idea of selling a few pages of a book digitally. As Jim Zarroli reported for NPR in 2005, there didn’t appear to be much of a market for this service and it didn’t take long for Amazon to discontinue this service.

“People don’t buy chapters,” the same participant added. “They do in education, but not in trade. It’s not to say that there isn’t some Napsterization of aspects of book publishing; I think for retail it’s not really relevant.”

Nonetheless, what happened with music and other entertainment formats was enough to have publishers concerned. As one executive with an ebook platform company recalled, in the early 2010s, publishers were extremely worried about the entire industry’s ability to be turned upside down by piracy.

“In 2021, 2022, 2023, they’re looking at it more from the point of view of subscription and streaming models and the change to economics that happens when you move from selling things one at a time to selling things through subscription services. So they seem to spend a lot of time thinking about the music industry.”

The focus on unauthorized file-sharing systems like Napster as a threat to ebook publishers overshadows the eventually successful, legitimate market for digital music. Today, music labels can distribute copies of music on platforms like Apple’s iTunes and Amazon’s MP3 Store and independent music sites like Bandcamp. These sites all sell music files to consumers, yet the publishing industry appears to have ignored these models in favor of more platform-based licensing approaches such as Spotify. While the experience of individual artists has varied significantly, the fact that the music industry has managed to stay afloat despite the loss of physical storefronts and albums, benefitting from new platform streaming models that depend on user subscriptions, digital ads, and data collection, has had an impact on the publishing mentality.

“Music went through some bumps, but now I would say the music industry is in a pretty great state, right?” an executive at an ebook subscription service platform said. “Between Spotify and Apple Music, there’s still a lot of subscription revenue out there for music. So I think there may be some bumps in the road in embracing the escription model, but I think that in the long run it’s going to be much better for the [publishing] industry for everyone to just embrace it.”

In some ways, fears that are discussed in the context of the music industry may really be anxiety about change more broadly. Multiple study participants that maintain professional relationships with major publishers recall publishers’ long-term reluctance to embrace the ebook format simply because it was outside their comfort zone.

Publishers Interpret Changes in Copyright Law As An Opportunity to Shut Down Secondary Markets

Courts have not settled on how to treat digital ownership, and publishers are taking advantage of this unresolved legal issue. The advent of digital technology has complicated and obfuscated the distinction between sales and licenses for digital goods. One reason that copyright is so complicated online is the way digital goods are copied. When physical books are copied, it is easy to quantify and track those copies. Each copy can be counted, lifted, stacked, and stored on a tangible shelf. Digital copies are much harder to quantify and track. With digital technology, there is rarely, if ever, a single copy of a work, even when the work is sold. Copies bought on CD or DVD are then loaded into the memory of a laptop computer. Downloads purchased via the cloud end up stored locally on a phone or tablet and across numerous cloud servers.

This rhetorical shift from ‘selling’ individual copies on digital media to ‘licensing’ a collection of multiple copies for use in digital memory began to obfuscate who controlled the digital item that was sold to the consumer.

Digital copies, even those purchased lawfully, often required a temporary instance of the software to be loaded into digital memory. As a result, copyright owners began to claim that a copyright license for these additional copies was needed to cover the copies of the work that existed in computer memory. This rhetorical shift from “selling” individual copies on digital media to “licensing” a collection of multiple copies for use in digital memory began to obfuscate who controlled the digital item that was sold to the consumer.

Even the notion of a “copy” soon became more metaphysical than physical in the world of digital content. The existence of a single “copy” became illusory, especially as modern computer storage systems learned to fragment even single files into thousands or millions of “shards” so they could be stored efficiently across various memory locations. Those same systems can make multitudes of ephemeral copies of files in the process of achieving mundane tasks like displaying the page of an ebook on a screen. Even if a consumer could argue that they owned the “copy” they bought, the tough question soon became: Where exactly is this copy? And how does the consumer find it if they want to resell it, lend it, or even give it away to a friend or family member?

Courts Begin to Weigh In

US courts struggled with how to think about the notion of a digital copy, and how to distinguish between a digital sale and a digital license. While some early courts were able to draw a distinction by analyzing a CD or DVD sale as controlled by copyright law and the installation of the digital content on a computer governed by whether a separate “contract” existed between the seller and the buyer, later courts could not make such clear-cut distinctions between copyright, which is governed by the First Sale Doctrine, and contract law-bound ownership arrangements, which are not.

In the summer of 2010, the US Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals heard three different copyright appeals, all of which turned on the notion of whether or not a consumer who had purchased or been gifted a digital copy could make independent uses of that copy against the wishes of the copyright owner. The first case was UMG Recordings, Inc. v. Augusto. The major record label UMG had a practice of sending unsolicited promotional (“promo”) CDs to DJs and other music fans. Troy Augusto, an entrepreneurial CD collector, would lawfully purchase used promo CDs and resell them, even though they often had a label on them stating “Not for Resale.” The second case was Vernor v. Autodesk, a similar case in which Tim Vernor bought and resold used copies of Autodesk’s architectural software program, AutoCad. Finally, in MDY v. Blizzard, the court heard a case as to whether purchasers of Blizzard’s World of Warcraft (WoW) video game infringed its copyright when they used a third-party “bot” program to autopilot their videogame characters through menial tasks in the game, a practice which Blizzard had forbidden in its game rules.

In each of these cases, questions of digital ownership were central. Despite the similarities among the fact patterns, the same three judges decided all three cases differently. Augusto emerged victorious, the court deciding that the lawful recipient owners of the promo CDs had a legal right to give their CDs to anyone and, thus, he had a legal right to resell them as he pleased. Vernor, on the other hand, was out of luck. The court decided that the Autodesk license was somehow stronger than the “Not for Resale” label on the CDs, and that digital software, oddly, was in some way inherently different from digital music, without saying exactly how. And in MDY, the court went a third way, saying that depending on the license term and language, the consumer sometimes had a right to use the software as she liked, and other times, she didn’t. It appeared that the terms copyright holders attached to digital media were important, although it remained unclear exactly how the power of terms interacted with the rights of users.

Then, in 2018, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals gave its own gloss on digital ownership. In Capitol Records v. ReDigi, the court considered whether a consumer who “bought” digital music songs from Apple’s iTunes Store had a right to resell them, and relatedly, whether the online marketplace ReDigi could help facilitate such sales. Here, the battle over rhetoric, technology, and copyright law reached a fever pitch. On the one hand, ReDigi had engineered a system that ensured the transfer of a music file securely from the seller’s computer to the purchaser’s without any extra copies being made. On the other hand, because the transfer was done through ReDigi’s cloud-based service, the transfer process involved making multiple intermediary copies of the original file, including the final copy on the purchaser’s computer. In deciding the case, the court interpreted this second digital location as a “copy” of the file, instead of a relocation of the original file from one computer to the other. And as such, that made the buyer’s copy an infringing reproduction of the song instead of a resale of the buyer’s copy.

All of this conflicting case law left quite a state of confusion for what it means to “own” digital goods. To some degree, that is still the case. The Supreme Court, to its credit, has tried to clarify in both a copyright case involving internationally sold used books and a patent case involving the reselling of printer toner cartridges that the First Sale Doctrine means just that – copyright and patent owners get to set the terms only the first time they sell a copy that contains their work. But, because neither case was entirely digital in nature, the conflict and confusion between the Supreme Court’s approach and cases like ReDigi, MDY, Vernor, and Augusto remains.

The vast majority of publishers have since taken advantage of this confusion, and have begun to insist that approaches like Vernor, which maximize the control that license terms can have on users, represent the current state of the law. What the US courts or Congress will ultimately decide on these issues and how that will impact digital ownership of ebooks remains to be seen. In the meantime, publishers continue to move forward on building a walled garden for ebooks built on licenses and technological limitations for consumers and cultural institutions.

Digital Distribution Changes the Economics of Book Production

Another murky area of the ebooks analysis is what it costs to publish an ebook. Is it more expensive to publish paper or electronic copies of books? Publishers sometimes claim that it is expensive to publish an ebook, but concrete numbers about how much ebooks cost to produce are hard, if not impossible, to find. Although reliable empirical data is limited, ebooks appear to be relatively inexpensive to produce when compared to physical books. One participant from a Big Five publisher stated simply that “Ebooks are easy to create in a form that everyone accepts as acceptable.” What that means, according to one digital sales representative at a Big Five publisher, is that the people who work on ebook files have to “design the file in such a way that it recognizes what device it’s being rendered on. We make sure that [the file] can be rendered on that device.”

This individual went on to explain that when file formats are not fully compatible across devices, text can display with unwanted spaces and characters that take away from the user’s experience. “When a book is designed, believe it or not, it’s like a work of art. We actually have book designers who actually design how fonts look on a page.”

A lot of our effort in print is dedicated toward optimizing that in terms of, you know, the paper that we acquire, the printing, space, transportation, shipping. None of that is required for ebooks.

A participant from a trade publishing association had a more nuanced view that comes across as more critical of the process: “Generally people see digital books as more expensive, but I would argue that they are not in terms of prep work, and that when it’s more expensive it’s because your workflow wasn’t built to support multiple outputs…. I’m keenly aware of what happens with digital formats when you first start trying to do them. You create a separate workflow with separate processes, you make more mistakes, things don’t work out, and then they kind of become calcified.”

According to an independent publisher, “If it’s a book with text, it just means creating a flowable epub file, which is not hard. If it is an illustrated book, then a fixed format epub is usually created, unless the publisher wants to pay extra for fancy features and custom coding.” Flowable epub files work across platforms because they are responsive and the text works and “reflows” in whatever device it’s being used on.

The relative economy of ebooks may also flow from the fact that ebook files are created once at the time of initial publication and then distributed in response to demand. One Big Five publishing house employee noted the inefficiencies inherent in the physical book distribution model when compared to ebooks: “A lot of our effort in print is dedicated toward optimizing that in terms of, you know, the paper that we acquire, the printing, space, transportation, shipping. None of that is required for ebooks.”

The economy of ebooks can also make hits especially profitable when, as a study participant from a trade association confirmed regarding ebooks, “the marginal cost is closer to zero.” A former Big Five executive also seemed to confirm this thought: “In an ebook, there’s no variable cost at all once you set up the system, right? You can put one book through, 100 books through, 50,000 books through. No additional cost, you’re just transferring files.”

Even if a book is a bust, there are still cost savings when publishers are dealing with the ebook format. In ebook publishing, there are no unsold copies. Publishing industry norms allow bookstores to return any unsold copies of a book to the publisher. In those cases, the publisher has paid to create the book, ship the book to the bookseller, return the book to the publishers, and destroy the copy. These costs do not exist when ebooks are distributed on demand.

Ebooks Reduce the Friction in Library Lending, Raising Concerns for Publishers

In addition to music industry-related fears, publishers are afraid that libraries lending ebooks will undermine the publishing business in a way that paper book lending doesn’t. Although some argue that ebook licensing helped increase access to broad digital collections during the COVID pandemic, ebooks and ebook licensing also limit the content and distribution of libraries’ collections.

In addition to visiting libraries to pick out paper books to take home, library patrons also use their library cards to access ebooks through websites that are made by third-party vendors and accessible on library websites. Instead of owning or controlling books, libraries sign digital library “access agreements” with companies like Hoopla, which select which ebooks library patrons can access and decide the terms of that access and lending for the libraries. These types of arrangements with ebook platforms worry library workers, who feel their roles are being replaced by the new vendors, or eliminated entirely. Other ebook platforms like OverDrive do let librarians handle decisions around collection development for ebooks because libraries can pick and choose individual titles. However, the same cost and restrictions still apply to librarians that use OverDrive.

Publishers Worry That Patron Lending May Undermine Sales

Publishers worry that one-click access through libraries will discourage readers from purchasing books. One participant from a Big Five publisher in digital explained, “What is the difference between, you know, say, there’s a new book coming out, and a customer has a choice to buy it on Amazon or log on at home and download it from their library for free? There’s much more incentive to download it for free and if there’s no limit to whether that book is available…. we don’t want everyone who wants to read [the] book knowing that they can get it through the library the same day and date of the release and they don’t sell anything at all.”

Publishers made a similar point in their lawsuit against the Internet Archive’s Controlled Digital Lending program. “The convenience of library ebook lending – particularly the ability to check out ebooks instantaneously, anytime and anywhere – makes it a highly attractive proposition to consumers who might otherwise purchase ebooks.”

This concern is often described as a lack of “friction” compared to physical book lending. It is rooted in the view that the ease of accessing books on ebook platforms like OverDrive’s Libby is now roughly equal to the ease of purchasing those same ebooks.

For the consumer, borrowing a free ebook from a library’s website, on the one hand, or obtaining it from Amazon or other e-retailers, on the other hand, are extremely similar experiences, except that one is free and one is not.

Participants associated with the publishing industry often drew a contrast between the similarity of the ebook purchasing and lending experiences on one hand, and the differences between the physical book purchasing and lending experiences on the other. However, those comparisons often exclusively attributed burdens to lending physical books that exist for purchasing physical books as well. For example, travel time and the possibility of a book not being available was often cited as a point of friction in library lending, while being essentially ignored for bookstore purchases.

A former executive at a Big Five publishing house used this framework to describe the friction involved with lending physical books: “If I’m a consumer in the old days, I could buy a book in the bookstore and read it. Or I could get in the car, drive down to the library instead of the bookstore, look to see if they had it. Check it out. If I hadn’t finished it in two weeks, I was going to have to bring it back. I was gonna forget to bring it back. I was gonna have to pay a fine. Oh, my kid lost it. Where the hell did that book go? Now I’m gonna get charged for the goddamn book and I don’t even have it.” While the post-check-out friction is specific to libraries, everything up to that point would also apply to the bookstore experience.

This concern was echoed by the senior VP of Grand Central Publishing (an imprint of Hachette) in the Internet Archive Controlled Digital Lending litigation. “We believe that the ‘friction’ involved in checking out physical books from libraries – the delays when a popular book is not available, the time and costs associated with traveling to the library to check out a physical book – may motivate some library patrons to purchase their own copy rather than check the book out from the library.”

While participants from the publishing industry often drew sharp contrasts between the lending and purchasing experience of physical books, they highlighted the similarity between lending and purchasing ebooks. The same executive continued: “Perhaps most importantly, the convenience of ebook lending – particularly the ability of users to check ebooks out instantaneously anytime and anywhere – makes it a highly attractive proposition to consumers who would otherwise purchase books instead of going to the library. Critically, the experience of checking out a library ebook is functionally identical to downloading a copy from Amazon.”

The chief digital officer at HarperCollins drew the same connection. “For the consumer, borrowing a free ebook from a library’s website, on the one hand, or obtaining it from Amazon or other e-retailers, on the other hand, are extremely similar experiences, except that one is free and one is not.”

A senior VP at Wiley expanded: “An ebook would be capable of far more efficient reproduction and distribution than a print book, allowing it to serve exponentially greater demand.”

Publishers are also concerned that library lending of ebooks will “train” readers that the value of ebooks is zero. This fear of training in the ebook market appears to be more acute than in the physical book market because of the publisher perception that ebook lending and purchasing is more similar than physical book lending and purchasing. The same former publishing executive explained: “And then the final significant danger is the deterioration in value. And that comes primarily through library lending. Right? The library lending issue is very difficult because it educates a whole group of people that books are essentially free.”

This concern about “free” books is echoed in the publishers’ complaint against the Internet Archive’s Controlled Digital Lending system: “[B]y providing copies of digital books for free, [the Internet Archive] devalues the book market. Consumers begin to view works as cheap and become increasingly unappreciative of what it takes to produce them and unwilling to pay fair value for them.” This concern is not unprecedented – music platforms have been similarly critiqued for devaluing the artists’ and labels’ labor.

The former publishing executive worries that nobody will buy ebooks if they can get an identical copy for free from a library. “And that lowers the amount of cash that comes into the system, which lowers the author’s advances, which makes it more difficult to be a publisher, and eventually makes it very difficult to make a living writing books.”

In conversations with participants, it was not always clear why publishers tend to view library copies of ebooks as “free.” Although these copies are free to patrons, they are available to patrons because libraries have purchased them from publishers. Increased patron demand for individual titles would encourage libraries to purchase additional copies from publishers. Publishers highlight that library acquisitions contribute to profits in their complaint against the Internet Archive’s Controlled Digital Lending program: “Harm to and loss of community support for public libraries, in turn, hurts the publishers, since these libraries pay for their books, which, in turn, hurts authors, who share in and depend upon compensation for their copyrights.”

In that same proceeding, one executive touted the growth of revenue in the library ebook market. “In fiscal year 2015, library ebook licenses in the United States constituted 2.3% of HarperCollins’ total US ebook revenue. By fiscal year 2020, that share grew substantially to 7.4% and reached 12.9% of all US ebook revenue by mid-2021. (HarperCollins’ fiscal year ends June 30.) Indeed, as of mid-2021, HarperCollins earned over $19 million in revenue from library ebook licenses in the United States, which was nearly twice as much revenue as we earned from library ebook licenses in the United States during FY 2020.”

It is not entirely clear how publishers understand the relationship between library acquisitions and retail sales. In a declaration that is part of the Internet Archive Controlled Digital Lending litigation, one publishing executive described conclusions he drew from OverDrive circulation data (the data and analysis itself was filed under seal). “While library ebook circulations made up 50% of the total units downloaded of trade ebooks between 2017 and 2020, ebooks obtained by libraries which resulted in those circulations brought in only 13% of total ebook revenue for Hachette…. The data discussed above has led Hachette to conclude that readers who were previously purchasing retail ebooks are switching to library ebooks, which means that we lose retail sales to free borrows.” Left unexplored in the publishers’ public analysis was how many of those library loans they believed replaced potential retail sales, how many loans per ebook publishers would view as reasonable, and how many loans per ebook libraries expect when deciding to pay for ebook access in the first place.

In one podcast, a Macmillan executive alleged that people used libraries to get around buying books: “I have a friend right now who has 11 library cards, never waits for a bestselling book, used to spend $500 a year on books.” Study participants affiliated with the publishing industry were often quick to point to that type of lost revenue when discussing library ebook lending in interviews. There was much less discussion of the impact that this type of patron ebook consumption might have on the acquisition decisions and budgets of the libraries used by those patrons.

Ambiguity Around Degradation Rates of Paper and Ebooks

Another concern that publishers shared was the fear that each electronic book copy is indestructible compared to paper copies of the past. Participants from the publishing industry often noted during our interviews that paper books tend to degrade physically, especially when they are shared. This was often contrasted with ebooks, which were commonly described as lasting in perpetuity. This industry understanding of the relative durability of books and ebooks – regardless of its veracity – raises questions about how to think about the value of a single copy of a book, in either physical or electronic form.

The physical fragility of paper books created an opportunity for publishers to resell copies of a popular title multiple times, especially to libraries, where books go through a lot of wear and tear as they are read by numerous patrons. As a former Big Five publishing executive explained, “Physical books fall apart. And they actually fall apart reasonably fast. Physical books get lost. Physical books don’t get returned to the library. So the library has to keep ordering the book every once in a while; think how many times your local library has ordered up Pride and Prejudice. Right? Since it was published. They’ve ordered a lot of copies of that book.”

The same former executive contrasted the fragility of physical books with ebooks: “Digital file, oh, that lasts forever. They buy it once, it lasts forever.” Another executive simply asserted that an ebook “does not degrade.”

While this sentiment was common among participants, it is unclear how accurately it reflects real-world dynamics. Popular physical books may wear out quickly, but copies of other titles remain in a library’s collection for years, decades, or even centuries, waiting for the occasional patron interest. When it comes to digital, publishers have demonstrated that they can create licensing schemes that require libraries to re-purchase books at a regular interval, or after a certain number of patrons check them out.

Furthermore, as anyone who has ever tried to open a digital file that is more than a few years old may know, the “forever” nature of digital copies is far from proven. The Internet Archive has described the work involved in maintaining its digital collection, in that it “processes and reprocesses the books it has digitized as new optical character recognition technologies come around, as new text understanding technologies open new analysis, as formats change from djvu to daisy to epub1 to epub2 to epub3 to pdf-a and on and on. This takes thousands of computer-months and programmer-years to do this work.”

It may be relevant that the nature of this degradation is not identical between physical books and ebooks. Physical books tend to wear out in a way that correlates with their popularity. The most popular titles wear out quickly, while less-popular titles may last in perpetuity (or at least until the acidic compounds in the paper they are printed on destroys them). In contrast, ebooks tend to become less accessible over time. All titles grow obsolete at the same rate, and all may disappear if the platform distributing them goes out of business. As that happens, the most popular titles may be the only ones that are replaced.

Regardless of their rate of decay, some libraries may devote resources to maintaining their digital collections, just as some libraries may devote resources to maintaining their physical collections. However, other libraries could adopt the same strategy for replacing outdated ebooks that they already use for worn-out physical books: purchase new copies.

Concentration and Consolidation Make It Easier to Push the Market in Publishers’ Favor

The changes in copyright law and technological realities have been unfolding against a backdrop of continued concentration within the publishing industry itself. This consolidation of power among publishers made it easier to avoid competitive pressures that may have prevented the ebook market from evolving in a way that is so different from the physical book market. It has also given publishers leverage in the ebook market to force libraries to follow their lead. This leverage is most vividly illustrated by examining the history of the terms that the largest publishers have offered to libraries.

Initially, ebook terms for libraries were relatively close to the rules that govern the first sale of physical books. As early as 2001, HarperCollins was offering libraries unlimited-checkout licenses to ebooks. While not quite a sale, this unlimited model looks remarkably flexible in retrospect.

2011 marks a shift in terms for many of the larger publishers. Citing “security concerns,” Penguin stopped offering new ebook titles via the OverDrive platform used by many libraries. Hachette also stopped offering frontlist ebooks to libraries, while also doubling prices for certain backlist titles. HarperCollins began capping ebook licenses at 26 loans. Once an ebook had been lent 26 times, a library could re-purchase the book at a discount. Macmillan and Simon & Schuster continued not to offer ebooks to libraries under any terms.

In 2012, Random House introduced a 100%-200% library ebook price increase on unlimited-use licenses. While this price increase did not come with an embargo that held new titles from library circulation, it did come with a request that libraries share data about patron borrowing patterns.

These license terms were adopted by Hachette in 2013, with library prices three times the consumer retail price for the first year after a book’s release. That same year, Macmillan began a pilot program to license its books to libraries, offering a license that was good for the lesser of two years or 52 loans. Simon & Schuster began its own library pilot program, which included a one-year license and a requirement that libraries act as sales agents by offering a “buy it now” option alongside ebook lending options (this “buy it now” requirement was removed by the end of 2014).

By 2020, all of the Big Five had shifted to some form of time-limited licenses (HarperCollins in 2011, Simon & Schuster and Macmillan in 2013 – followed by a shift back toward a limited perpetual approach in 2019 and a reintroduction of time limits in 2020, Penguin Random House in 2018, and Hachette in 2019). These terms were slightly modified during the early phase of the COVID pandemic, although it is unclear how and if they will persist going forward.

This evolution away from licenses that simulate ownership toward licenses that simulate ongoing rentals is especially noteworthy in light of the constant pushback publishers received from one of the license’s primary markets: libraries and librarians. The American Library Association “expressed concern” when Hachette moved away from perpetual licenses in 2019. ReadersFirst described Macmillan’s reintroduction of library embargoes for new titles as “A Giant Leap … Backwards” (ellipsis in original). Librarian Sari Feldman’s Publishers Weekly column on the same topic described it as “A Dystopian Twist.” A viral blog post by Sarah Houghton, director for the San Rafael (California) Public Library, compared the “dismal ebook situation in libraries” to a bad boyfriend.

None of this activity has pushed any of the Big Five to compete by adopting the model that a significant number of their customers appear to demand. Instead, over the course of almost two decades, these publishers have moved toward models that give them more control over how ebooks are used, and more opportunities to shift toward recurring revenue streams.

The Publisher-Platform Partnership Shapes the Ebook Market

The physical book market is largely shaped by balancing the interests of two stakeholders: publishers and purchasers. While bookstores play an important part in that market, the First Sale Doctrine tends to limit their permanent influence: A bookstore’s relationship with a physical book ends the moment that it is sold. Deciding to shop at a new bookstore does not involve re-purchasing all of the books you purchased from others.

Balancing interests in the ebook market is more complex. In addition to publishers and readers, ebook platforms have ongoing interests in how ebooks are created, distributed, and controlled. Those interests exist independently from the interests of publishers and readers. Licensing allows ebook platforms to exercise that influence in an ongoing manner. In many (although not all) cases, publishers and platforms find their interests aligned when it comes to shaping the ebook market. This publisher-platform partnership rebalances the playing field in the ebook market, tilting things away from purchasers and toward the publishers and platforms.

The result is an ebook market that is designed to support the preferences of publishers and platforms, at the expense of the interests of the purchasers. It replaces sales and ownership with licenses tying ebooks to both publishers and platforms in perpetuity. These perpetual ties also create new opportunities for publishers and platforms to monetize reader data by spying on ebook readers.

While locking purchasers into platforms serves some interests of both publishers and platforms, that lock-in has unique impacts on publishers, platforms, and purchasers.

Digital Rights Management Technology Creates Lock-In

Licenses are the legal tools that platforms and publishers use to control how purchasers can use ebooks. Digital Rights Management (DRM) is the primary technical tool used to implement that control, sidestepping first sale rights. Publishers and book platforms use DRM to prevent consumers from downloading, saving, sharing, and other common first sale-permitted activities. DRM tools make it very hard, if not impossible (and possibly illegal), for users to move the ebooks in their collection between platforms and ereaders. If a consumer licenses access to a book on Kindle, they cannot open that file on a NOOK, or on any other platform or app.

The full motivations behind implementing DRM are not always entirely clear. Many participants connected DRM with concerns about large-scale piracy. At the same time, they also noted approvingly that DRM would prevent casual lending between friends. (One publishing executive even stated that DRM played an important role in ensuring that local library spending benefited local members of the community.)

While sometimes conflated by participants, stealing books and sharing books are distinct activities in the world of physical books and first sale. Printing and distributing multiple, unauthorized copies of a physical book would violate the copyright in that book. In contrast, sharing the single copy of the book you purchased with a friend would be well within your rights under copyright law.

Although the DRM benefits both publishers and platforms by reducing purchaser control over ebooks, participants suggest that the use of DRM is driven primarily by publisher demands. None of them suggested that DRM was being driven solely by the platforms. Applying DRM is a major condition for publishers to work with ebook platforms at all.

“From a retailer perspective, we still believe it’s the publisher’s problem and not so much ours,” a digital director at an ebook platform company said. “If the publisher says, I will not give you these books unless you get with the times [and implement DRM], let’s say the industry is going in a certain direction. So then we would have to do software updates to support that. But we as a retailer are not driving that decision. We would just support where it goes.”

While DRM may be driven by publisher demands, it benefits platforms as well. Several participants agree that customers get hooked into ebook platforms and say the inability to easily transfer ebook files between different platforms, particularly with Amazon, makes it difficult for customers to switch between platforms, leading to a further concentration of market share among a few dominant players.

“With ebook, there’s Digital Rights Management on ebooks so you just don’t have the cross-pollination across platforms that one would hope for,” one participant said. “If you buy from Kindle, you cannot play it on a NOOK, you cannot play it on a Kobo device, so when you’re in the ecosystem of a company, that’s pretty much where you stay.”

Participants’ mixed views on the purpose of DRM tracked responses reported by industry analyst Mike Shatzkin over a decade ago. In an informal survey of “[n]ine very high-level executives in seven different top dozen publishing houses, plus four literary agents with extremely powerful client lists,” Shatzkin reported that “[e]leven of the 13 agreed with me that DRM is necessary to protect sales. Ten of the 13 agreed with me that DRM is not an effective deterrent to piracy. And 12 of the 13 agreed with me that DRM’s main benefit is to prevent casual sharing!” Respondents then, and study participants today, understood that DRM’s practical effect was preventing the type of casual sharing between friends that is allowed under the First Sale Doctrine, and that DRM is not an effective anti-piracy measure.

One participant, who is an executive at an ebook platform company, explained how DRM is meant to limit the legal transferability of ownership, and not just prevent illegal piracy. “Nobody wanted there to be a secondary market for ebooks, and I think mostly because nobody could imagine how you would control it or because you’re dealing with perfect replicas, like how do you ever keep that in the box?” the participant explained. “So the focus was on maintaining the perimeter through DRM, rather than a focus on ownership structure that could just prove to be impractical to try and enforce.”

The DRM placed on ebooks, when combined with ebook licensing schemes’ limitations on first sale uses, can collapse the distinct activities of ‘lending’ and ‘piracy’ into a single violation of the license.

The DRM placed on ebooks, when combined with ebook licensing schemes’ limitations on first sale uses, can collapse the distinct activities of “lending” and “piracy” into a single violation of the license. In doing so, the DRM, and licensing limitations, can use the pretext of preventing an illegal activity (large-scale copyright infringement) to restrict a legal activity that has long been disliked by some publishers (loaning a copy of a book to a friend).

One participant at a Big Five publisher explained it like this: “We want customers to be able to read the book, to keep the book forever. What we don’t want [is] to have someone take that ebook file and then share it with 10,000 other friends for free.”

During the Internet Archive Controlled Digital Lending proceeding, the senior VP for Online and Digital Sales at Penguin Random House also conflated the ability to lend an ebook to a friend with worldwide piracy: “If the ebook could be shared among devices belonging to multiple users, the cost would be significantly higher to reflect the broader distribution. And the price to purchase an ebook file, without restrictions on its further use or distribution, would be utterly unaffordable as a practical matter given that it could potentially satisfy global ebook demand for that title.”

Copyright law prohibits a single user from sharing a single ebook with 10,000 friends. DRM does as well. However, only DRM prohibits a user from sharing a single ebook with a single friend.

The concern that individuals lending books might undermine sales was explicitly described by other participants as well. “So I think it’s a conflicted sense around whether ebooks are good for publishing and good for the industry and whether or not they’re kind of providing the basis for either undermining sales because of consumer sales by making it easier to lend and sometimes undermining sales because of piracy,” said the participant from the trade book association.

As another participant in the digital side of one of the Big Five publishing houses explained, “[publishers] license because they want to make sure there is an artificial lifespan on the file, and an artificial cap on the sharing of that file.”

Many participants appeared to believe that DRM does effectively prevent unauthorized copies of ebooks from appearing online. A former executive at a Big Five publishing house explained that “If there weren’t enough protections, and the plain fact of the matter is, you know, 50 or 60% of the books out there were pirated, readily available for free, essentially, copyright would be gone.”

Whatever other benefits DRM may bring to publishers, publisher insistence on applying DRM to ebooks has also undermined the development of a more-competitive platform landscape.

Another participant in a director role at a platform company echoed this sentiment: “Once a book is out there in the world, there’s nothing to stop it from going viral. Especially, certainly, you’re never going to see that happen with a John Grisham or James Patterson [book]. … There’s no way that they would make that DRM free.”

Both of these doomsday descriptions fail to account for today’s reality in which the majority of DRM-protected ebooks are already illicitly available online.

Other industry players appear to have less confidence in DRM as an anti-piracy tool. In January 2023, International Publishers Association (IPA) President Karine Pansa claimed that the fear of unauthorized distribution of ebooks was keeping entire regions out of ebooks despite the existence of DRM: “In Africa and the Arab world, we hear publishers saying that they won’t shift to digital because the risk of piracy is too great and their copyright enforcement regimes want to protect them.”

Regardless of its actual effectiveness as an anti-piracy measure, DRM has effectively reduced readers’ freedom to own the books they pay for.

Finally, DRM creates a somewhat striking dynamic between publishers and the platform companies. Whatever other benefits DRM may bring to publishers, publisher insistence on applying DRM to ebooks has also undermined the development of a more-competitive platform landscape. It is notable that even though there are clear benefits to platforms when DRM is used to lock purchasers into specific walled gardens, the industry consensus is that the use of DRM is driven by the publishers themselves. Publishers’ decades-long focus on eliminating the secondary market may have led them to insist on technology that locked them into a handful of platforms.

Platform Companies Use Walled Garden Infrastructure to Make Purchaser and Publisher Lock-In Profitable

Ebook platforms lock in publishers and purchasers by building digital walled gardens, while simultaneously collecting data from both parties. Ebook platforms lock in publishers with their distribution agreements, and they lock in users by allowing people to see ebooks only on the platform where they were originally purchased (and prohibiting downloading, sharing, and other off-platform access). This lock-in is in the interest of platforms, and creates some benefits for publishers. However, when it comes to walled gardens, the long-term interests of publishers and platforms may not be fully aligned.

Platforms leverage license agreements that prevent purchasers from taking their books outside the digital garden walls. This makes platforms sticky to purchasers. Once a purchaser has one ebook on a platform, they are likely to return for a second, third, and so-on. That allows platforms to convert their walled garden structure into increased ebook sales.

Ebook platform lock-in has specific impacts on libraries. Some platform schemes require libraries to pay for bundles of publications instead of picking out their own books. Before digital content was provided on internet-connected platforms, libraries had robust “collection development” teams tasked with reading through book reviews, advertisements, and other recommendations to curate their library collections title-by-title. That old model has been replaced by the modern digital platform model, in which a continuous stream of “content” is available on every library visitors’ “feed.” In public libraries, these content collections can contain titles that are downright offensive or incorrect – in 2022, some librarians noticed that Hoopla, an OverDrive competitor, was platforming Holocaust denial propaganda and books containing incorrect information about reproductive healthcare, LGBTQIA issues, and other similarly problematic works.

As one collections development librarian at an academic library told us, this purchasers’ mindset discourages libraries from sharing digital resources and developing unique collections: “Every single library that I know of was just throwing money at the problem [during the pandemic]. Like, fine, we’ll get all of the Project Muse ebooks. Fine, we’ll get all of the JSTOR ebooks. And so we just funneled money into these publishers, but we couldn’t actually be like, okay, [my library’s] buying all of Johns Hopkins so that Yale can buy all of JSTOR and we’ll just lend. Like we couldn’t do that. We all just bought the same stuff and that’s terrible from a collection development standpoint.”

This study participant believes academic libraries are united in thinking this approach isn’t working, to the point that some university librarians are turning their collection focus back to purchasing print books: “Because [print books are] a for-sure thing, like there’s a physical object. We can lend that physical object,” the study participant added.

Libraries may choose not to participate in the ebook market because of what they perceive as restrictive, and sometimes seemingly exploitative, terms of use. The platform providers tack on digital bells and whistles to the items they sell, like product-related metrics, customer ratings, and algorithm-driven “see more like this” options. These data analytics and algorithmic features add value to the copyrighted material by giving consumers extra information about the content they’re viewing, but they are also tools for publishers to assert more control over the materials they provide to consumers. By embedding add-ons into items that used to be sold outright, publishers can claim that the raw material of their publications are inseparable from the platforms and metadata they’re attached to.

Walled garden platforms are uniquely poised to provide their owners (or those with access to their data) a ‘God’s-eye view’ of their consumers’ habits, preferences, and decision-making tendencies.

As discussed in more detail below, these features are also tools for personal data collection and use. Walled garden platforms are uniquely poised to provide their owners (or those with access to their data) a “God’s-eye view” of their consumers’ habits, preferences, and decision-making tendencies. Publishers can use customer ratings and other consumer feedback to intuit what particular users will want, based on their data, and predict what they will buy in the future, and to decide what books to publish and what prices to charge.

Publishing Platforms Also Lock In Publishers